Portfolio Optimization and Analytics Results

Investment Policies

Investment policies are the gearbox of the optimization engine. Historical data needs to be reshaped and refined to maximize its predictive efficacy. These refinements are designed to produce more accurate estimated inputs. Numerous techniques exist to estimate risk, return, and correlation inputs. These are the required inputs of mean-variance optimization. Diversification Optimization shares the same inputs. Following are a few things we did to improve the predictions.

For each optimization’s anniversary date on Aug. 1, we would select two sample periods for the historical data. The first sample period was the previous one year; the second sample period was the previous 10-year period. The baseline risk, return and correlation values are calculated for every asset as the average of these two periods. We believe these two periods merge a positive predictive momentum signal arising from the one-year data with the stock’s performance over at least one full market cycle in the long sample. We tested staggered multiple optimization intervals and found no material effect. We applied the sampling procedure uniformly over all sectors and years.

In this research, and in accordance with our best practice methodologies, we apply a James-Stein shrinkage (Stein, 1961) process to the multisample historical risk and return data. This process applied uniquely to both risk and return, allows the portfolio architect to think of risk, return, and diversification as three separate dials in the portfolio construction process. This allows you to weight risk and return data in their proper proportions. The more shrinkage that is applied to a return value, the more normalized the range of return. As such, it diminishes the role of returns in the optimization when compared to diversification or the chosen risk metric. Likewise, the same result occurs if the risk value is shrunk more. In this research, we shrunk the risk values with a slightly higher coefficient than the returns values, effectively—albeit slightly—deprioritizing the assets’ semi-variance when compared to the estimated returns.

Figure 8 shows what happens as real-world portfolios from macroaxis.com are graphed using the actual risk and return values obtained: The positive association of risk and return is no longer apparent. The ex-ante relationship vanishes ex-post.

Fundamentally, risk and return are not two separate things, but the same. Risk is simply negative returns (Figure 9).

This foundational tenet is always obvious to investors in retrospect. Nevertheless, there are widespread errors in risk estimation, definition, and application across the entire industry. Risk cannot be known in advance; it must be estimated. In a risk-based weighting scheme, any such estimation faces the impossible task of measuring the known unknowns and the unknown unknowns. One may liken risk measurement to holding a tape measure around a black hole without succumbing to the event horizon.

There may be some salvage value in risk minimization, certainly from diversification, but also from simple avoidance of the riskiest elements of the market. The most volatile decile of the Russell 1000 constituents underperformed the full index in the subsequent year by 8.52 percent for the period 1972 to 2012 (Ghayur, 2013).

One of the traditional methods of portfolio optimization and construction is mean-variance optimization (MVO), which was pioneered by Harry Markowitz in the 1950s (Markowitz, 1952). Markowitz and the variations he has spawned have had significant application in our industry, but they have only recently gained traction as index construction methodologies.

There may be some salvage value in risk minimization, certainly from diversification, but also from simple avoidance of the riskiest elements of the market. The most volatile decile of the Russell 1000 constituents underperformed the full index in the subsequent year by 8.52 percent for the period 1972 to 2012 (Ghayur, 2013).

One of the traditional methods of portfolio optimization and construction is mean-variance optimization (MVO), which was pioneered by Harry Markowitz in the 1950s (Markowitz, 1952). Markowitz and the variations he has spawned have had significant application in our industry, but they have only recently gained traction as index construction methodologies.

MVO’s focus on volatility fails to exploit an asymmetric diversification/return relationship (Damschroder, 2009). Furthermore, diversification is shown to have greater stability in a crisis (Damschroder, 2009).

How to Interpret Portfolio Optimization and Analytics Results

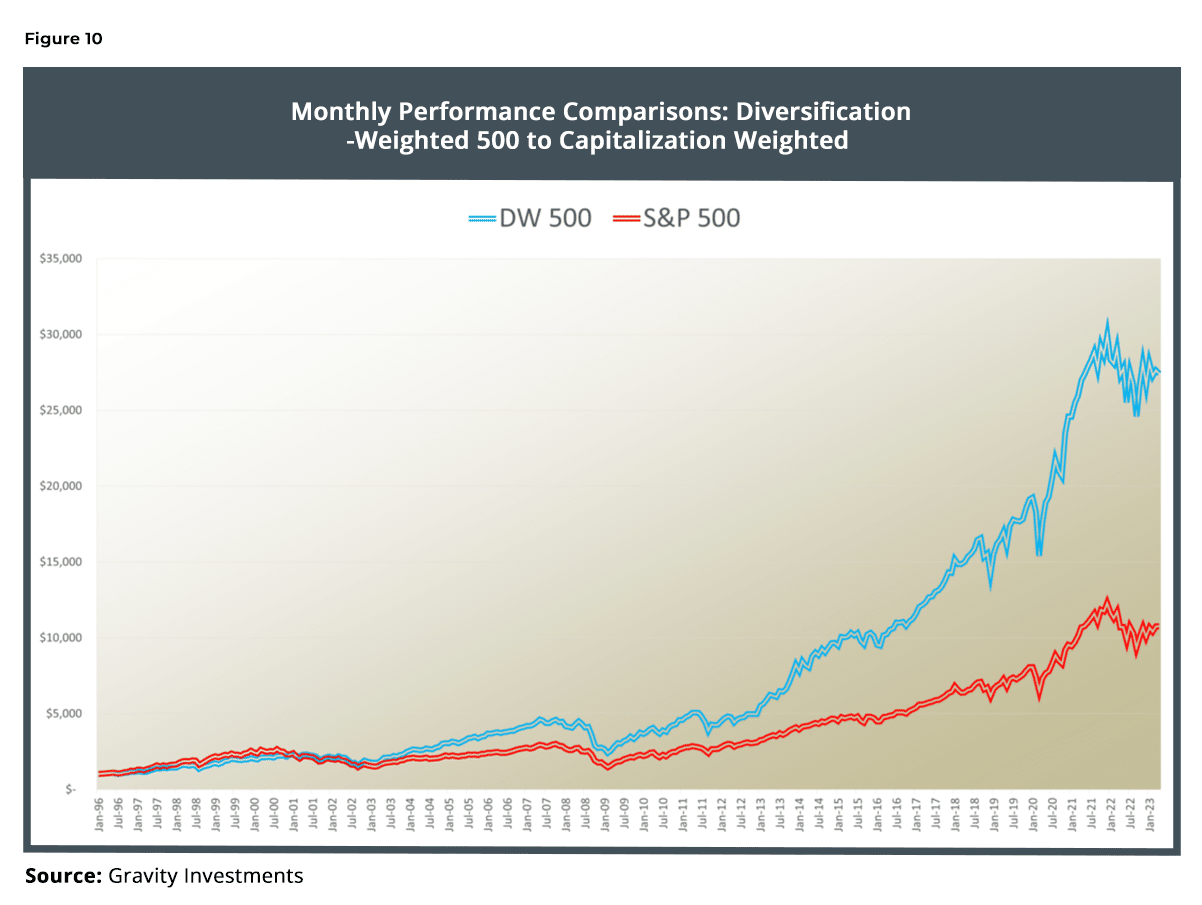

In aggregate, the Diversification Weighted 500 outperformed the S&P 500 index by 427 basis points per year (Figures 10 and 11). The Diversification Weighted strategy is reported net of fees, estimated at 90 bps, and net of an estimated 20 bps trading cost.

Diversification looks to have had its worst relative year in 1998, despite putting up a 17.7 percent return. In calendar year 2008, DW was 80 bps under the S&P 500 Index despite having a few percent better drawdown through the crisis. While over the entire crisis the DW strategy did better, it also had a worse losing month, losing 3.43 percent more than the S&P 500 in October 2008.

The full-sample upside- and downside-capture statistics for the DW 500 are:

Up Capture: 105 percent Down Capture: 87 percent

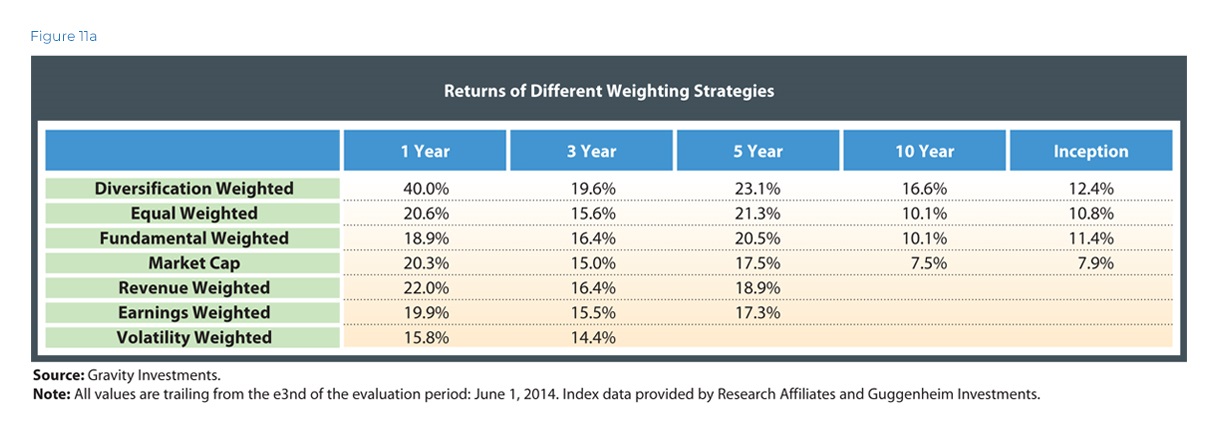

Clearly, the performance looks good against a capitalization- weighted approach. What about other weighting approaches?

(See Figure 12.)

The equal-weighted and fundamentally weighted strategies are reported gross of fees and trading cost. The remaining assets are based on the ETF products, which report net fees. Dividends are reinvested. Before 2010, the DW 500 sectors and sector comparisons have their daily returns adjusted to receive the S&P 500 annual dividend yield (http://www.multpl.com/).

Risk Analysis

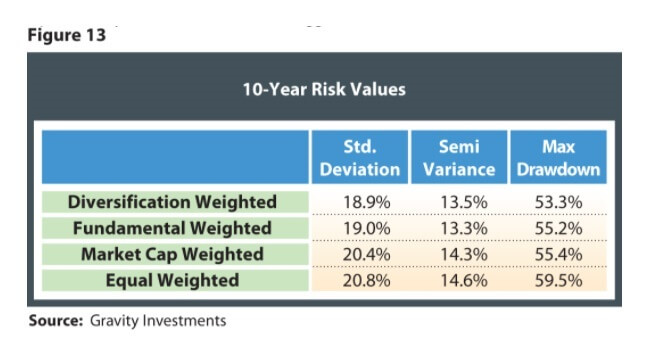

A few weighting approaches were excluded from the risk table in Figure 13, as the maximum drawdown statistic requires comparable histories for accurate comparison, and risk stats for any product having not lived through the crisis of 2008 seem trite.

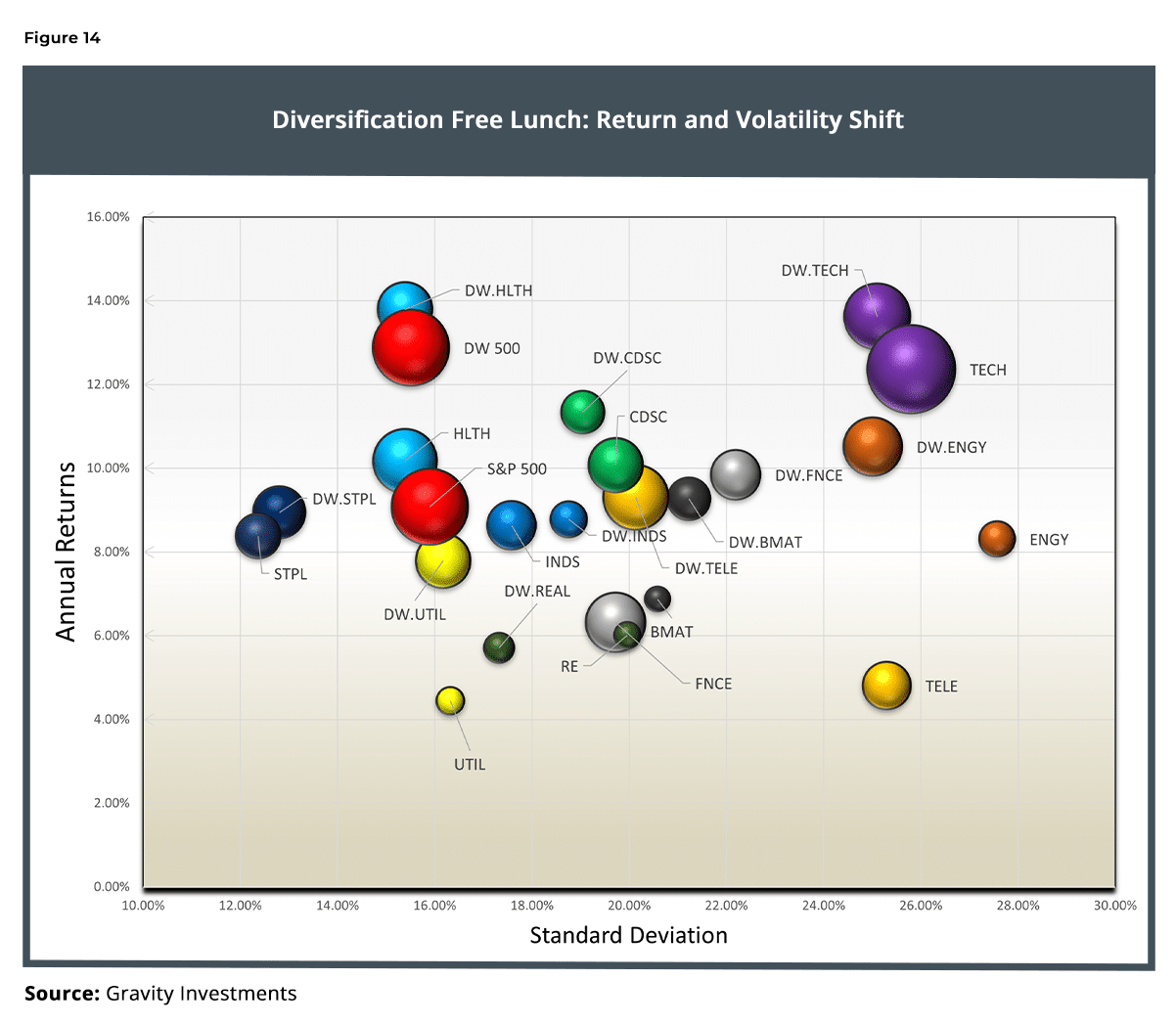

To the chagrin of efficient market theorists, the diversification Weighted strategies in most cases produce higher returns while lowering the portfolio variance. This hypothesizes massive market inefficiency, perhaps induced by the trillions of dollars attached to capitalization-weighted approaches.

5 sectors with greater return and less variance

4 sectors with greater returns and more variance

1 sector with smaller returns and less variance

Diversification Returns &

Diversification Alpha

Diversification goes both ways. Most investors intuit the benefit of defensive diversification, but diversification can play offense, too. The defensive ability of diversification to protect capital is a function of the noncorrelation and is available to all investors in any strategy. Diversification as a proactive strategy is comparable to a rebalancing bonus. The sum of the defensive and offensive performance capabilities of diversification is what we call the “Diversification Alpha.”

The alpha is made possible by exploiting diversification, volatility and some sort of trading activity, such as rebalancing, but it can be other activity such as reconstitution or reoptimization. This trilogy of portfolio variables combines the idiosyncratic asset volatilities to produce alpha.

More rebalancing, more diversification (noncorrelation), and—contrary to modern portfolio theory—more volatility are all catalysts to increase this level of alpha. The effect is a veritable profit ratchet, which relates to Parrondo’s paradox (Stutzer, 2010). This strategy is implemented at some large investment managers, such as Parametric and Janus Intech. Our index construction technique enables a more efficient capture of the diversification ratchet due to the optimization’s direct focus on diversification.

The diversification-ratchet is very similar to a rebalancing bonus; however, the diversification-ratchet is a more appropriate moniker because the alpha is available to investors without rebalancing. Other forms of portfolio activity produce the alpha, including reconstitution, reoptimization, profit-taking, stop loss, trimming, and even dollar cost averaging. In all cases, the alpha requires diversification. In this research, we had annual reconstitution and annual reoptimization, no rebalancing, and the strategy was able to benefit from the diversification-ratchet.

Portfolio managers get the defensive contribution of diversification whether or not they try to. The driver is the amount of correlation exploited. In Diversification Returns and Asset Contributions, Fama and Booth (1992) coined the term “diversification returns,” which represents an additive portfolio return attributed to diversification. Booth and Fama approximated this as half the variance reduction in the portfolio given by diversification. The weighted average asset variance would be the portfolio variance if the correlations were all 1. For the most recent Diversification Weighted 500, the weighted average asset variance is 9.35, corresponding to a standard deviation of 30.57 percent. The portfolio variance is 3.41 percent, corresponding to a standard deviation of 11.64 percent.

As this shows, the incremental return is a function of the amount of variance reduction; it is not a function of the actual level of the portfolio variance. For example, if you start with low-volatility assets, say, having a weighted average standard deviation of 9 percent, the covariances in the portfolio serve to further reduce the portfolio standard deviation to 8 percent. The diversification return is (.09−.08)2 = .857 percent. While the portfolio may claim a low variance, the diversification return of 86 bps is a fraction of the 297 bp diversification return obtained by the DW 500. If your focus is variance and not correlation, it limits the amount of variance reduction, and thus the Diversification Alpha.

Stacking Diversification

The Diversification Weighted 500 and this article are introducing the idea of a stacked rebalancing bonus. Diversification may be woven in at multiple levels in a portfolio. By stacking the Diversification Alpha at multiple levels, it is possible to produce a purely additive performance gain. This research demonstrates the effect by optimizing within each sector and optimizing the sectors again for the composite.

In Figure 15, the Diversification Alpha is larger at the security level due to the higher volatility and lower correlations of the individual securities.

While beyond the scope of this research, it would seem to be further possible (and likely) for a third alpha stack working at an asset class and/or country level.

Sector Analysis

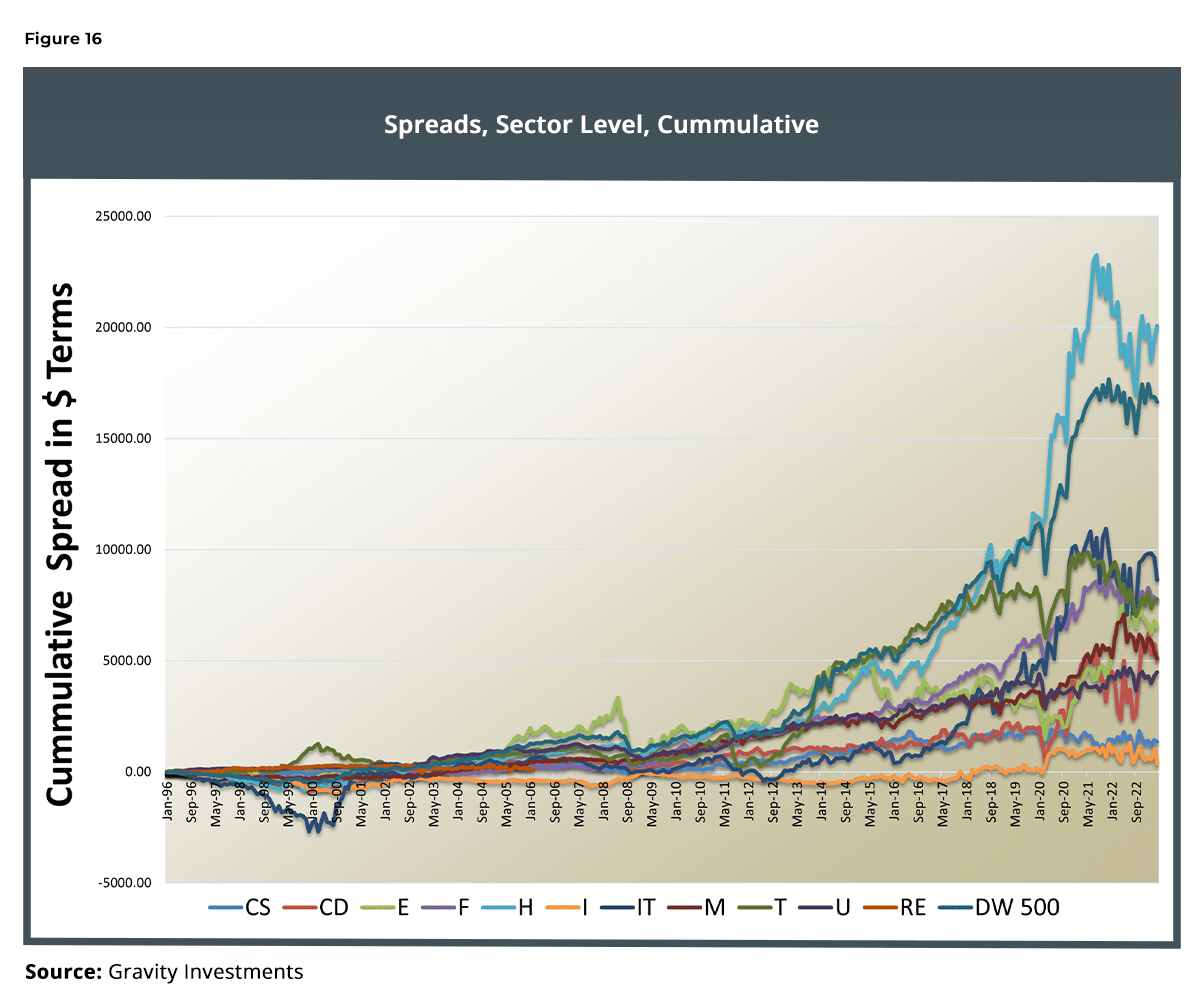

In Figure 16, each of the line-graphs represents the relative performance of the diversification-weighted sector and composite indexes with regard to their cap-weighted counterparts. Only the industrial sector underperformed. Curiously, the diversification-weighted technology sector showed material underperformance during the late 1990s. When a market-leading sector or industry arises, we have seen the worst available correlations come from that leading sector. As a result, unless otherwise neutralized by stronger expected performance, it is the diversification process’s natural tendency to underweight the market leader segment.

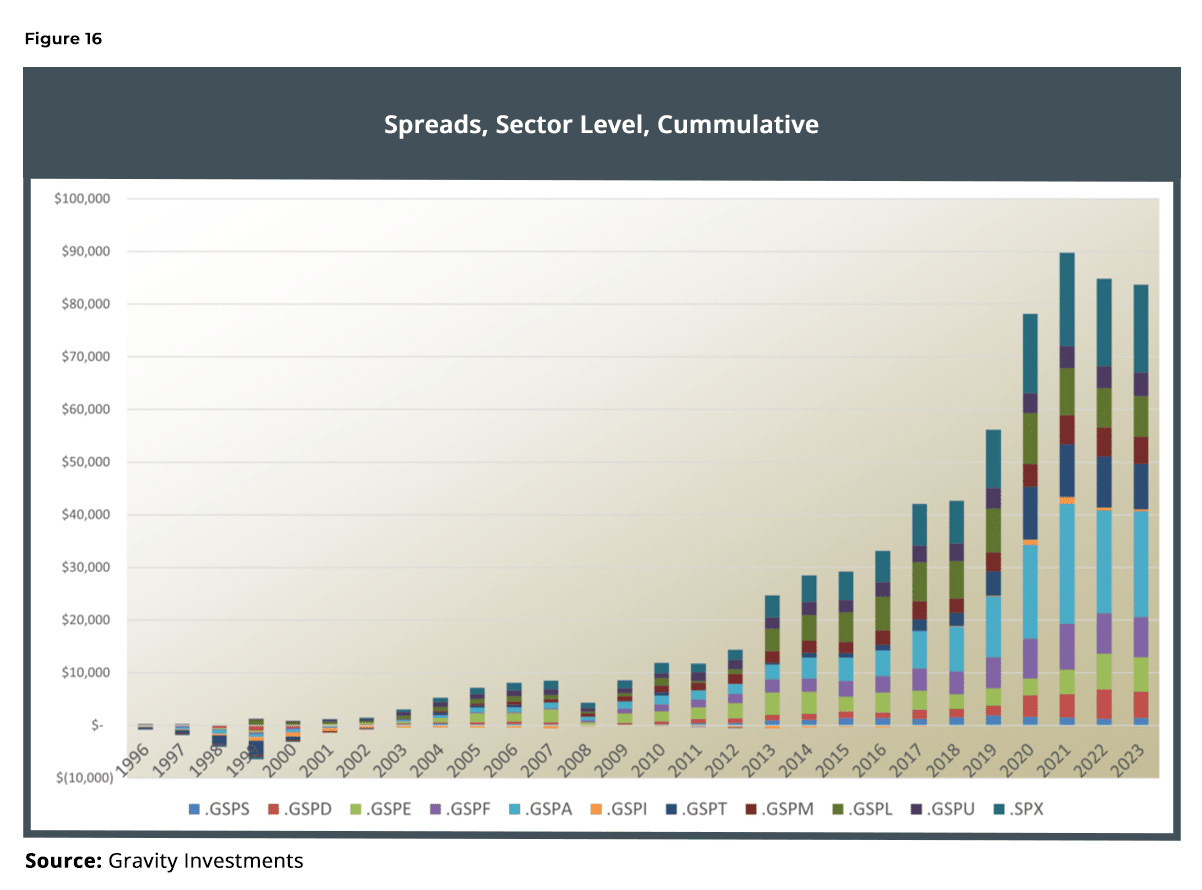

Figure 17 includes a stacked chart to help illustrate the consistency of the incremental performance for each sector over time.

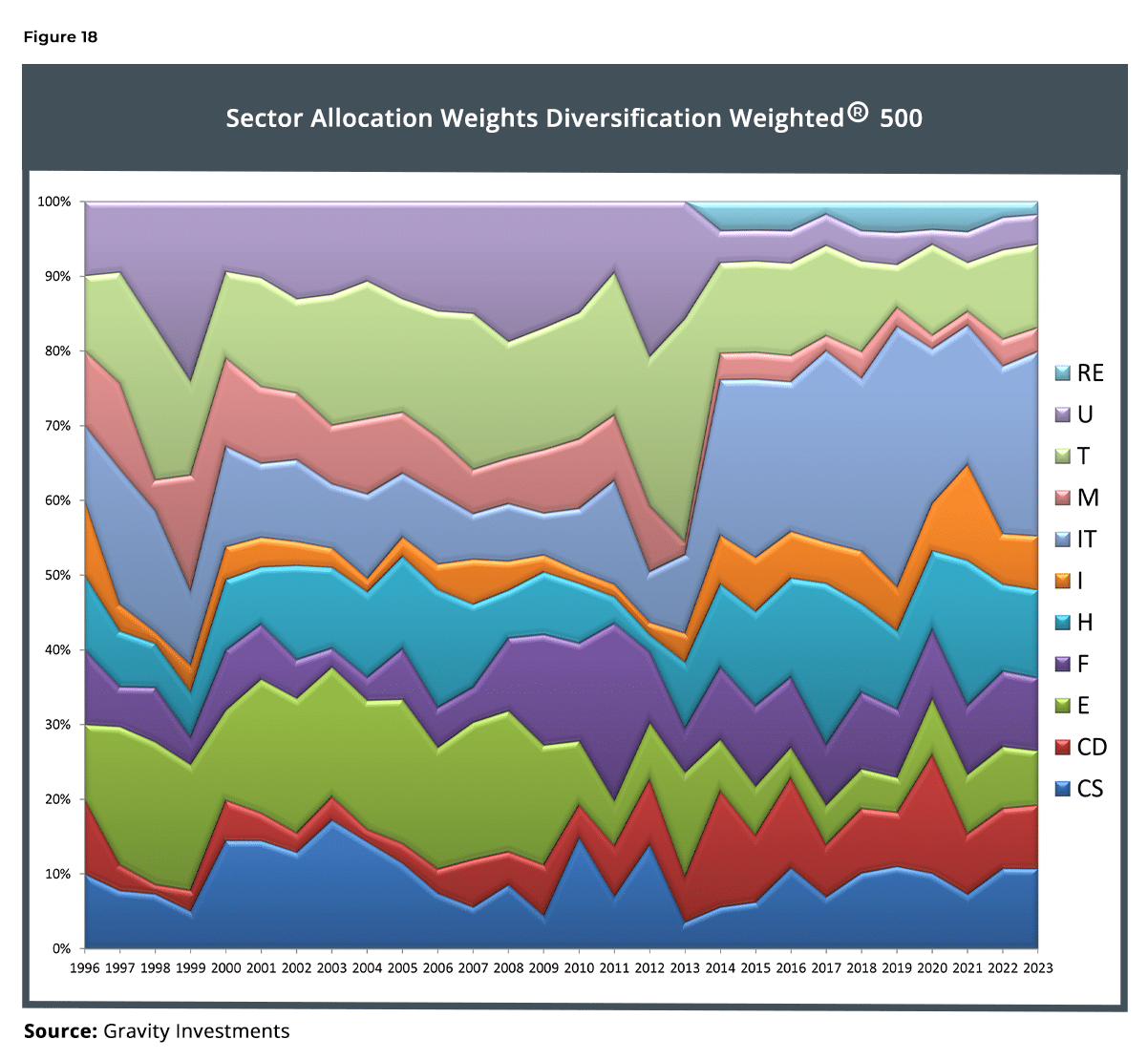

The sector allocation also reveals an interesting and intuitive dynamic: Whenever the market heats up, asset correlations tend to come in, leaving the investor with relatively fewer diversification sources. Telecom and utilities are the largest active weights of the Diversification Weighted strategy over the whole period.

We observe in Figure 18 that allocations to these less alluring sectors have increased going into a market peak. These investments have acted as an automatic buttress to the portfolio-elevated systematic risk. This underscores an interesting behavioral tenet: diversification, systematically applied, works as a check on emotional overreactions and is a way of imposing systematic and sound investment discipline into the strategy.

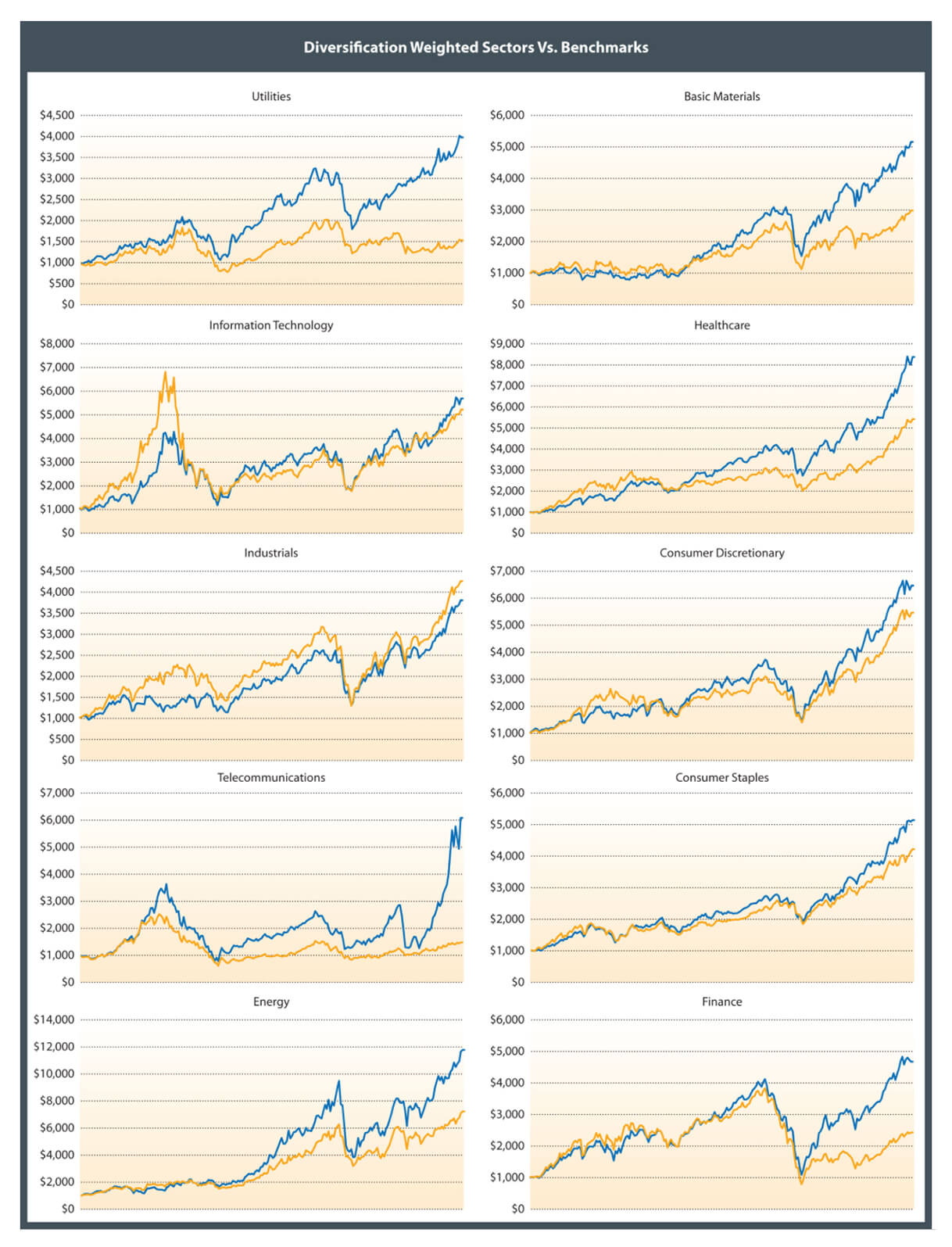

Investors in a diversification-weighted strategy seem to enjoy a fair amount of consistency in performance. The relative consistency of the sector weights over time is a positive indicator of turnover control. Consistency appears both over time and across the sectors. The Diversification Weighted 500 sector sleeves beat their benchmark in nine of 10 instances (Figure 19).

MPT And Factor Analysis

The DW 500 shows an R2 of.80 for a single-factor market risk and an R2 of.83 for a five-factor model. It had statistically insignificant factor exposures to size, momentum, and the risk-free rate. The value factor gave a positive exposure, with a coefficient of.23. For the analysis period, value paid investors 2.09 percent annually, which boosted the returns to the DW 500 by 49 basis points. We expect this is an artifact of the focus on diversification.

Value companies by their nature have a greater proportion of idiosyncratic performance when compared to growth, which often shares homogenizing factors such as cyclicality (data is from the Ken French website (French, 2014)).

Crucially, the Diversification Weighted 500 produced 652 bps of alpha per year on average for more than 18 years. The alpha for the five-factor model is 414 bps. The statistical significance of the beta-factor alpha is observed having a P value of.00014, or a chance of the alpha being obtained randomly less than 1 in 7,000.

Remarkably, the alpha was demonstrated purely by the weighting approach, as the product had naive security selection, no timing, leverage, shorting, hedging, or other positional risk management, and invested in all the same underlying components of the benchmark.

Attribution Analysis

The full-period attribution analysis shows that the Diversification Weighted 500 actually lost 274 bps compared to ending sector weights.

This means that the alpha produced by the strategy did so with a 274 bp head wind at the sector level.

Sustainability And Capacity

Diversification Weighting carries with it a theme of sustainability not found in any other weighting scheme except fundamental weighting. A weighting scheme is an allocation scheme, and an allocation scheme inherently matches providers of capital (investors) with demanders of capital (companies). Diversification lives in the crevice of finance. Any two mega-cap companies are globally interwoven into the mesh that buoys the correlation of the two and decreases their diversification potential. Value companies have a greater proportion of idiosyncratic risk and thus tend to enjoy lower correlations compared with growth companies. Imagine a world where capital formation is free of the massive head winds of regulation and scale, afforded to a few thousand public companies that can shoulder such overhead. The correlation of entrepreneurs, ideas, and execution provides an infinite pool of diversification sources, and we hope that diversification optimization drives capital in the most beneficial way.

Is the world ready to put trillions of dollars into diversification? Weighted strategies? What about capacity constraints? Will the alpha erode with assets? Naturally, expected returns and other assumptions vary greatly from investor to investor.

You can imagine that diverse investor expectations across strategies and platforms may help alleviate matters of moving the market. Whether the DW 500 or another DW strategy—be it equity, asset allocation, currency, fixed income, or funds of funds—Diversification weighted models may likely continue to perform as the massive macro inefficiencies induced by behavioral volatility (overreaction) and passive capitalization approaches appear to provide plenty of ammunition capable of sustaining the performance of Diversification weighted strategies into the future.

Conclusion

The Diversification Weighted 500 demonstrates material and consistent outperformance against other weighting approaches and within the sectors sleeves that we consolidated into the composite.

We explain a framework for diversification measurement and optimization. Diversification Optimization builds on this framework, and the results contrast favorably versus other weighting approaches. We quantify the Diversification Return at 2.97 percent, and we introduce the Diversification Alpha. Total alpha for the strategy is 652 bps annually for over 18 years. We further introduce the ability to stack the Diversification Alpha at the security, sector and asset class level.

The flexibility and efficacy of Diversification Optimization, combined with the demonstrated consistency, attractive risk metrics and total return, presents a strong case for the institutional application of Diversification Weighting as an overlay weighting strategy, product-sleeve, core-satellite model or index.

Disclosure

This portfolio is hypothetical. This is a historical simulation of the portfolio performance an investor would have obtained had you invested in the same selections at the beginning of the simulation. This report provides information on how the portfolio holdings would have changed and would have performed for a certain period.

We have strived to reduce or eliminate potential biases in the process to provide the most accurate assessment of the performance prospects of the strategy. Because Portfolio ThinkTank offers a significant However, it may not be possible for any historical simulation to completely ensure it is free of all biases.

Please see The Gold Standard for Portfolio Backteting and The Seven Deadly Sins Of Portfolio Backtesting for a more complete understanding of biases and risks when backtesting portfolio strategies.

Backtested strategies also run the risk of cherry picking. Cherry Picking is when the author of the backtest has created many variations and is presenting one of the variations that is more favorable. This research was not produced in whole or in part by cherry picking.

This simulation is based on an account with tax exempt or tax deferred growth. Taxable accounts will have to pay the appropriate taxes for dividends, interest and capital gains, which will decrease the performance depicted.

This simulation is not based on actual trading accounts or account composites which may or may not exist for this strategy and may be materially different including worse than the performance illustrated above. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future performance. Performance results including risk, return and diversification measures are not guaranteed to persist in the future.

This historical performance simulation has been adjusted to reflect estimated management fees.

The suitability of this portfolio strategy requires that you have thoughtfully and accurately completed your investor objectives from your accounts’ Investment Policy Statement. Portfolio Think Tank Login Diversification strategies alone cannot assure a successful investment outcome. Strategies offering greater diversification cannot guarantee any reduction in loss of capital.

Your ability to follow this investment strategy is a risk. Investors often dispose of successful strategies at inopportune times thus turning potentially profitable strategies into losses.

Portfolio data is taken from sources believed to be accurate, however, there is no warranty or guarantee as to the accuracy or completeness of data and statistical calculations thereupon. Our performance results are not audited or otherwise approved by any regulatory agency. We regularly perform quality and accurate tests on our calculation and algorithmic procedures. Portfolio ThinkTank does not furnish investment advice without an investment advisory agreement.

The period of time selected for analysis may have a significant bearing on the relative attractiveness of the strategy and the strategy versus another portfolio or benchmark. The author of the strategy controls the default period of time used to analyze performance and from there, users may select any desired period of time from the menu. In general, longer periods, greater diversification and lower concentrations of holdings result in more credible, more persistent performance.

We are unaware of any errors at the time of writing.

References

Multpl.com. (2014).

Booth, David and Eugene Fama. (May/June 1992). “Diversification Returns and Asset Contributions.” Financial Analysts Journal, vol. 48, No. 3, 26-32.

Damschroder, James. (2010). Internal research report.

Damschroder, James. (2014). “Systematic Risk Exposure of Weighting Approaches,” working paper.

Damschroder, James and Haoyan Sun. (2009). “How True Diversification Preserves Capital.”

French, Kenneth. (2014). Data Library. Retrieved from Darthmouth: Data Library.

Ghayur, Khalid (2013). “Low Volatility Investing.” Burridge Center Conference at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Markowitz, H. (March 1952). “Portfolio Selection.” The Journal of Finance, vol. 7, No. 1, 77-91.

Markowitz, H. (July 2010). private conversation. (James Damschroder, interviewer)

Stein, Charles and W. James. (1961). “Estimation with Quadratic Loss.” Fourth Berkeley Symposium. Berkeley, California.

Stutzer, Michael (Spring 2010). “The Paradox of Diversification.” Journal of Investing, vol. 19, No. 1, 32-35.

Swensen, David. (2005). “Unconventional Success.”